Saturday morning I was making ceramics with a friend when Rosie the guard dog started barking, an urgent pitch. Stepping outside to investigate, I found a car in the driveway, three strangers inside.

“Your son’s been in an accident,” one said urgently. “Up the road. You have to come.”

Around seven million thoughts shot through my mind, the first being confusion and the second uneasy relief. I knew my son was nearly 2,000 miles away in Brooklyn. I told the messenger she must be mistaken but she insisted that someone at the crash site had clearly told her to come to the Tiny T Ranch to get me. So, if not Henry, who?

I contemplated other possibilities. My friend Brandon had just left. Was it him? Or maybe one of my tenants? Swiftly I sent out an APB demanding everyone report in. Everyone replied they were fine.

Back inside, adrenaline coursing through me, I grabbed my keys and updated my friend. She offered to drive. A good idea. It took us less than two minutes to reach the crash, a half-mile from the ranch, traffic at a standstill backup. I hopped out and moved toward the wreck on foot. It wasn’t looking good. A destroyed small car and, in a nearby field, a StarFlight Helicopter waiting to rush its driver to hospital. On the other side of the road a kid, maybe eight or nine, sitting in a daze, his grandmother standing over him, apparently the occupants of the truck that had been hit.

A deputy stepped forward and intercepted me. I explained the odd situation, saying I had been sent for, told that someone I knew was part of this tragedy. But even as I spoke, I could see this wasn’t true.

As I walked back toward my friend’s car, I again came upon the folks who had raced to get me. Befuddled, I asked them again, and then again, if they were sure that whoever sent them had said, “Tiny T Ranch.” They were adamant.

I have not yet solved this creepy mystery, and I doubt I ever will. But as I spent the rest of the day trying to calm myself, my mind, which likes to look for messages in odd places, seized upon something.

Your son’s been in an accident.

I realized that, any time I reflect on my son’s childhood, most often my conclusion is—if not precisely in these words—Your son’s been in an accident. As if I had gotten every single moment of mothering wrong. As if I had ruined his life irreparably, simply by being the mother to whom he was born. As if his only experience in life was and remains profound suffering. As if every pain he has ever felt and ever will feel is somehow my fault, directly or indirectly.

Intellectually, I can vaguely grasp that this is untrue. But when I try to counter this negative, self-imposed guilt trip, try to make myself recount things I did get right, in from a dark corner slithers some warped message from long ago about how making such positive tallies (perhaps especially by women) is just another way of fucking up, of trying to deny or cover up all the bad stuff and also, since I’m piling it on, is also a version of that deadly sin, Pride.

As of today, I have been a mother for 34 years. I could spend endless hours and countless words laundry-listing my Mothering Mistakes. I’m roughly 100% positive that a major driver of this self-denigration is, just like the road to hell, paved with good intentions. Like so many of us, one of the biggest mistakes I’ve made—and still sometimes make—has been trying to foist upon my adult child not necessarily what he needs, but what I needed and never got.

My own mother never could—and has made it abundantly clear she never will—acknowledge my childhood trauma. It doesn’t matter to her that she was standing inches away when my “father” hit me in the face. It doesn’t matter that even the despicable catholic church recognized (in the form of a financial settlement) that I was sexually assaulted by my cousin priest. She will hear none of it. And so, not out of anger but frustration and sadness, I can no longer communicate with her

Last year, right after Sinead died, I watched the beautiful documentary about her. In one scene, she is being interviewed by a TV host about how her mother beat the living shite out of her regularly and damaged her permanently. She was in her early twenties at the time. This was the ‘80s, before phrases like PTSD and intergenerational trauma were tossed around as they are today. But even then she understood, expressed compassion for her abusive mother, who’d learnt violence from her own mother, who’d learnt it from her own mother and so on, like some nightmare version of that old Faberge shampoo commercial.

How that stuck with me. My mother’s mother’s mother died when she (my grandmother) was a little child. Her stepmother beat the hell out of her. Then her father died and my grandmother, still a child, was sent to who knows where, separated from her siblings. She married at sixteen, had seven kids (one died), and one of her tools of discipline was an electric cord that she used to beat her kids. Her husband, my grandfather, was a violent drunk, often unemployed, and so my grandmother waited tables to support her family, which was a perpetual struggle.

My mother began a correspondence with my “father” when she was fifteen and he was twenty and away in the Korean War. She eloped at 19, outraging her parents. She didn’t beat us with an electrical cord, but there were those moments in which hairbrushes and “the Big Spoon” were employed to make us fall into line. Honestly, I have scant memories of being beaten. I focus more on all the arts and crafts she taught us, fostering in me a lifelong passion.

When I consider her history, the time and culture into which she was born, her home life as a child—I can actually (almost) understand how my “father” was always a hero to her, her own father having set the bar so terribly low.

How harshly I judged her throughout my life for having lied to herself and us kids about what a great guy he was. And so my comeuppance, which took a very long time to arrive, was sharp and agonizing when it did. For my own son’s father split when he was two, languished in alcoholism so severe he regularly had seizures, sent no child support. And yet, year after year after year I loaded my son into one beater car or another, drove him to St. Louis to see this man, and perpetuated the lie that he wasn’t “bad,” he was just very sick. Technically, these were truths. He is not a bad man—he is certainly kinder than my father. But the message I was trying to convey was some myth that he was a really, really good guy, and he didn’t mean to fail as a father. I was so locked into this presentation that I refused to see and believe that no matter why he split, the fact is he split, and no abandoned child ever just “gets over it.” He might not be a bad man, but he was a terrible father. Or, more accurately, no father at all.

This unwanted realization brought with it another urge to spout a cascade of apologies upon my son as I realized my attempts at sunniness regarding his biological male parent just added to whatever else he has had to deal with when trying to sort through the wreckage of having an absent father.

But then, on the other hand, had I gone the opposite direction, cut that guy out completely, painted him as a worthless drunk, presented negative commentary, surely this choice, too, would have brought with it unwanted consequences, perhaps fostered another kind of resentment.

I know, from experience, the apologies that I have offered—often when I am in some heightened emotional state centered on sorrow and regret—come with their own risks. Because at some point, perpetual apologies can easily shift—even if unintentionally—from being about the recipient and turn into a narcissist-adjacent quest on behalf of the issuer to be granted some blanket “forgiveness” (what a fraught concept).

Though I have gotten much better at not haranguing my son with apologies, I still sometimes slip up, get tangled up in waves of regret, cannot control the impulse to try to articulate everything I wish I had done differently. The last time this happened, he stopped me. I was crying, the words were pouring out of me, I was so distressed. Quietly and calmly he asked me to please stop trying to process his trauma. He reminded me that was his job and that he had plenty of tools in place to work on his stuff.

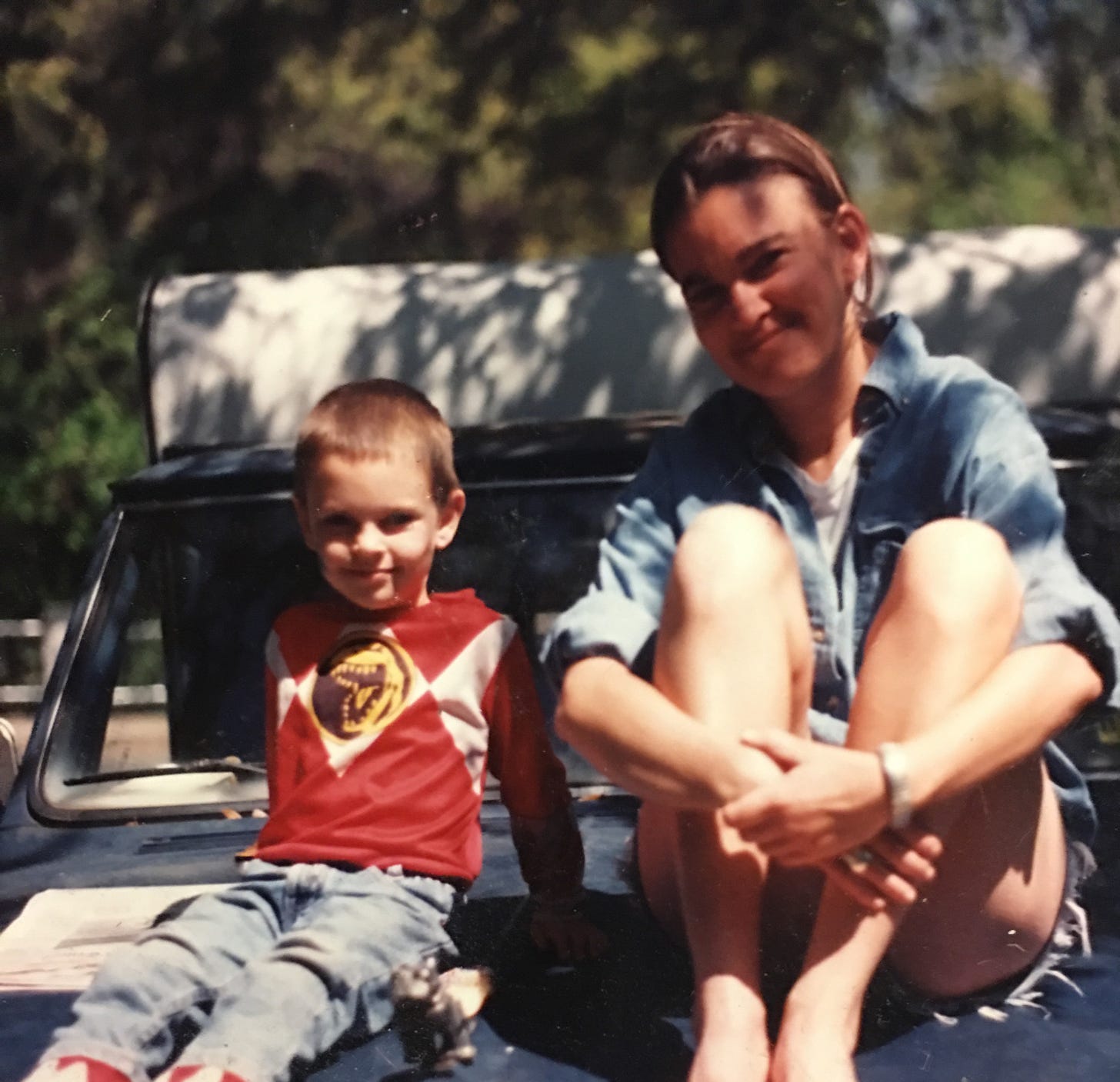

This, in and of itself, was instant, undeniable evidence that surely I had not gotten everything wrong. Plenty of other evidence abounds. For my son has found more than a small measure of meaning and joy in his life. He is passionate about his art, for which—though this isn’t important to him—he has received some impressive accolades. He is an accomplished musician. He is a kind soul who fosters hard case dogs and feeds the homeless. He is a good man.

Today, for his birthday, I am going to focus on the gift he gave me, and try to set down the rumination on all my failings. In turn, I know this will be my gift to him. His hope is that I will live and enjoy my life, find peace in my days. This, I understand. It’s the very same thing I wish for him.

NOTES

Thanks for reading y’all. Welcome all the new subscribers. If you can swing a paid subscription for $5 per month or $50 per year, please consider it. Your support really helps. If you can’t swing $5 per month, you can still help by sharing this with others.

Exciting news—my new book, Grok This, Bitch, is now available in Austin at Reverie Books, a groovy little shop with a wonderful old school feel. You can also buy direct from me. $10 gets you an e-copy. $30 gets you a print copy (postage included). If you want a copy, you can Venmo me: @spike-gillespie.

My next FREE writing workshop at Hampton Branch Library is tomorrow, Dec 3rd, 5:30 - 7:30. It always fills up. To reserve a spot you can RSVP here.

I continue to volunteer at the Central Presbyterian Church, feeding and clothing our homeless neighbors. If you have adult clothes, shoes, blankets, towels, etc, to donate, I’d be glad to take them off your hands and distribute them. You can email me so we can schedule a pick up/drop off.

A wise person after I told her I did my best with my kids said but they deserved better.

That’s my understanding. Our parents did their best but we deserved better.

Thank you for so eloquently describing mother's guilt. I'm happy that you and Henry have found peace with the past.